private accounts invites the reader into “spamcom,” a community using Instagram as a collective diary. Spam accounts in this setting go against the popular conception of Instagram as an inauthentic platform that does not provide insight into users’ “real” everyday experiences. Instead of the “highlight reel” synonymous with the “main Instagram” culture, spams can be a lowlight reel, where people turn to share their life stories: detailing painful breakups, reckoning with sometimes life-threatening mental illnesses, or sharing mundane experiences at school or work. These two senses of low—unglamorized emotional pain and evidence of a less financially indulgent life than the bikini pictures on one’s main Instagram suggest—make up an alternative form of sharing, and an inherent protest of the culture Instagram prescribes.

To be invited into the spam community and able to view these posts, an Instagram user is expected to have a private account of their own that they are willing to reveal in exchange. The content sourced for this documentation was only accessible because of the artist’s own mutual relationships with the people whose posts she engaged with in the book. These posts are presented in ways that aim to anonymize their creators, while revealing a collective story.

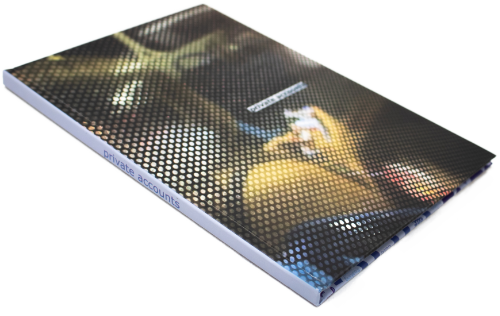

private accounts treats the spam content much like spamcom itself does, using strategies that reveal and conceal the vulnerabilities present in posts. In generously cropped images and captions, readers get a sense of the community's visual content, emoji, sentence structures, and themes. Wordclouds created from raw caption data show the prevalence of certain words like “fucking,” “coffee,” and “like.”

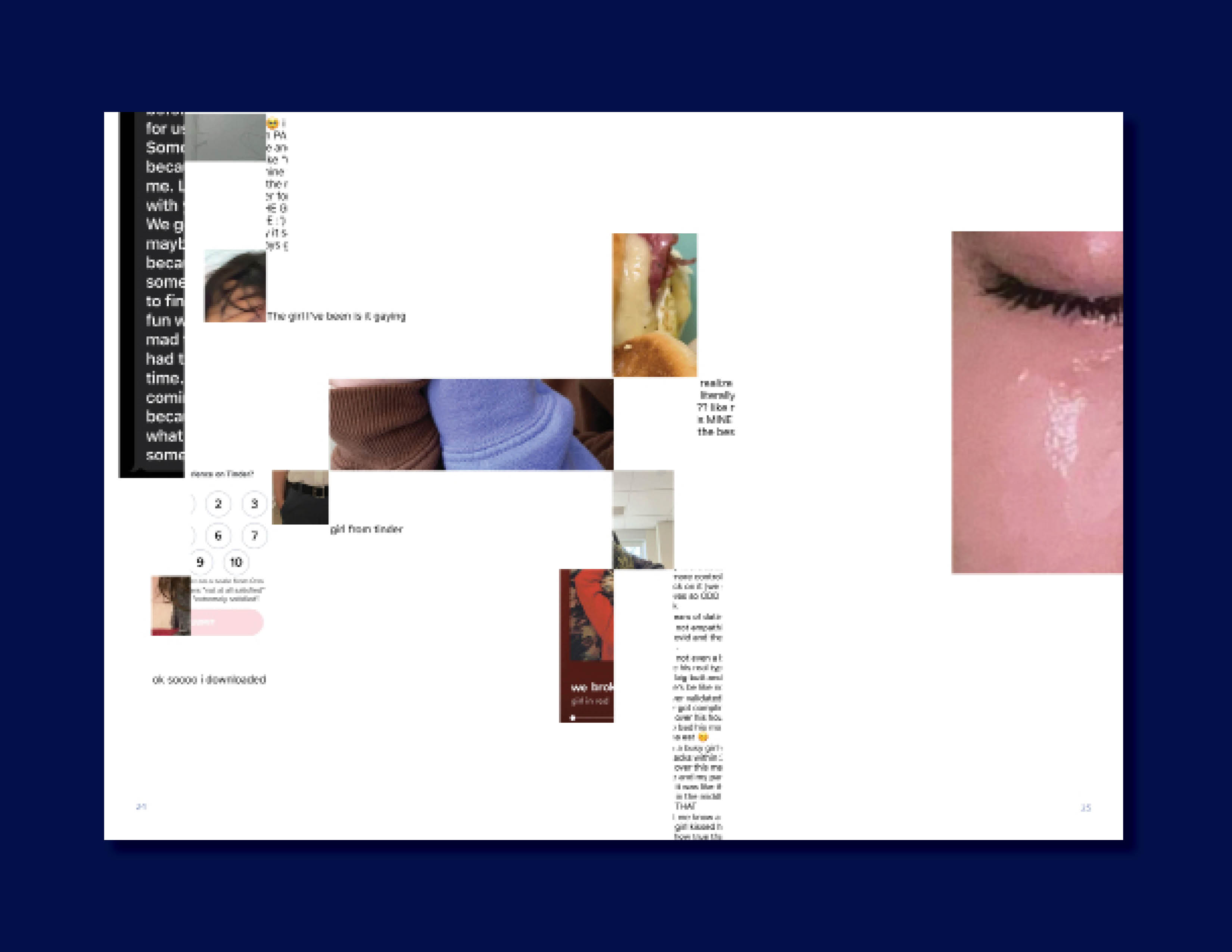

The artist also engages in an at times combative experiment with the AI text generator Chat GPT that spans the length of the book. While Chat GPT can easily rewrite the content of a series of posts, it is unable to mimic the language of the spam community. This could be because it is preserved behind private accounts, because it does not make anyone any money, or due to a simple lack of statistical prevalence on the web.

Rather than making any conclusive statements, private accounts functions as an artist’s documentation, providing a window into a specific group of people who share demographic traits (largely female, 18-24, queer) and interests (indie music, post-ironic memes, coffee drinks). As “girls” online, spam posters are part of the larger world of “girl internet,” which is arguably where most internet culture lies. When spam users post, they come together as girls and become part of a collective visual and written language which transgresses the values embedded in Instagram as an application.

Unlike a traditional diary, where writers address their entries to the object of the diary, spam posters address their entries to a community of their peers. On an interpersonal level, spam account owners are tasked with curating their followers, and reckoning with the fact their posts could be screenshotted and shared widely without their consent. These screenshots—like the ones in this book—can live on longer than any post itself.

The internet is simultaneously very easy and very difficult to archive. While it cannot go down in a fire like the Library of Alexandria, the obsolescence of hosting websites and of software like Flash can result in loss of knowledge from only years ago. Organizations like the Internet Archive strive to preserve public sites and discourse, but preserving private accounts is left up to the user. The prospect of archiving other people’s protected media without their consent raises obvious concerns over privacy. Taking on all necessary ethical baggage, private accounts places its subject’s sensitive information into a more traditional hiding place—between its pages.